Fiona Young

Fiona YoungOn 25 March 2020, Fiona and Ben Young drove to their local maternity unit through London’s empty streets. When they arrived, security guards sent them to the back entrance. It was day three of England’s first lockdown and the front was surrounded by patients being treated by doctors in hazmat suits.

Two days later, after a long labour, they welcomed baby Elijah. Delighted and exhausted, they left the hospital and headed home, full of anticipation over their new life as parents.

But because of lockdown, it was far from what they expected.

“No-one was allowed to visit us for months – there were no newborn cuddles with family,” Fiona recalls.

“I had a number to ring if there was an emergency, which didn’t work. We had no health visitor and no midwives. Our first visitor was a friend who walked four hours across London to sit in our garden.”

Elijah, now four and about to start school, is one of tens of thousands of babies born during the Covid pandemic. He is also one of 200 children being studied as a ‘lockdown baby’.

The Bicycle (Born in Covid Year, Core Lockdown Effects) study, which launched in July, is looking at whether the lockdowns had an impact on children’s talking and thinking skills.

Based at London’s City University, it also involves five other English universities.

“Some children may have benefited from more time at home with their parents and some children might have been negatively impacted,” Prof Lucy Howell of City University explains.

“They may be learning words more slowly or their fine motor skills may possibly be behind.

“The real question is: who was affected and what can we do to support them as they go into their school lives?”

Reduced interactions with family members and the loss of access to services such as health visitors has had a serious impact on the speech and language of some of these children, initial research by the University of Leeds found at the end of 2023.

In Bethnal Green, London, twins Aqil and Fawaz were just eight weeks old when the pandemic hit.

Their mother, Fahmeda Ahmed, lived in a second-floor flat with her husband and their two older children – Hasan, four, and two-year-old Khaijah.

“It was just the same day over and over again,” she said. “We couldn’t go out, we couldn’t socialise, we couldn’t invite friends over and we couldn’t go anywhere with the kids.”

Fahmeda bought an inflatable swimming pool for the balcony to try and keep her older children entertained.

She attempted to homeschool her four-year-old, who had just started reception, but he completely stopped talking.

And then there was baby Aqil. He was having difficulty swallowing and Fahmeda tried for months to get a face-to-face appointment with a doctor.

Eventually, at three months, he was diagnosed with tracheomalacia, a condition where the walls of a child’s windpipe collapse. He needed a minor operation.

“I was so scared going into the hospital because you would hear stories that you would catch [Covid],” Fahmeda said.

“And I remember when Aqil was going into theatre, I was so upset. There was a nurse there and she said ‘I’m so sorry. I can’t hug you’.”

Four years on, Aqil and Fawaz are healthy young boys, about to start reception at Elizabeth Selby Infants’ School in Bethnal Green.

But they both have speech and language needs.

Their two-year child development check was delayed, they weren’t able to attend any baby classes and their first year involved very little interaction with the outside world.

Fahmeda believes all these factors have had a lasting effect, and experts agree.

“Children need opportunities to go out into the world and have new experiences and with those new experiences come new words – but that is happening less during the cost-of-living crisis and it happened less during the pandemic,” says Jane Harris, head of children’s charity Speech and Language UK.

Prof Catherine Davies, from the University of Leeds, who is also involved in the study, says many of the safety nets for families like Fahmeda’s were taken away during the pandemic.

“The education systems weren’t there, health and medical support was not there, their interaction with their wider social networks wasn’t there,” she said.

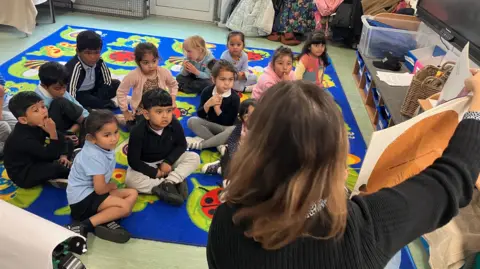

One third of pre-schoolers (34%) at Elizabeth Selby had speech and language needs during the last school year – up from a quarter (25%) in 2020, according to the school.

This year, the school has had to employ a speech and language therapist for its pre-school class for the first time.

In June, 22,952 children were waiting 19 to 52 weeks for a speech and language therapy appointment, and 5,832 children were waiting over a year, according to NHS England.

“If I could, I’d have a speech and language teacher in five days a week – and I would still have a waiting list,” says Shahi Ahmed, head teacher at Elizabeth Selby.

“But I have to think about the budget and how that impacts the school.”

Mr Ahmed says there is a “massive increase” in the number of children needing help with toilet training, which takes teachers away from teaching. The school is now bringing in outside agencies to help support parents.

And among all of this, attendance is falling, which Mr Ahmed says is important as it sets “routine and expectations”.

Mr Ahmed believes the increase in children needing more help is “absolutely” a direct result of the pandemic.

“They didn’t have the chance to interact with other children or even just go out or have visitors to the house,” he says.

“They’ve been limited to what’s around them – and that has caused a gap in their social interaction skills.”

Thankfully, Fahmeda says her twin boys have already benefited from their time in Elizabeth Selby’s pre-school classes.

“Fawaz has changed completely – he never used to call me mum,” she says, wiping her tears away.

“It’s so nice to hear. You might think I’m being silly, but that’s so amazing and it’s because of the teachers.”

As for Elijah, his first interactions with family members were all on Zoom.

“We would hold up the iPad to his face and introduce him but he wasn’t really paying much attention,” Fiona said.

“I think he saw the lights and colour but I don’t think he understood he was meeting humans.”

He didn’t attend any baby classes as they had all been cancelled. “He spent the first three months solely with us,” she said.

Elijah was diagnosed with tongue tie when he was born. Fiona and Ben were told by a midwife that they would be better off getting tongue-tie surgery, also known as a lingual frenotomy, privately, as there would be a long wait on the NHS.

“The first day I came back from hospital I was phoning around frantically to find someone who could do it privately but no-one was allowed to physically come in – it wasn’t legal for them to come in and do the operation,” Fiona explained.

Elijah finally had the operation when he was two-months-old.

Katie Monnelly

Katie MonnellyThe long-term impact of Elijah’s early years remain to be seen but it was certainly a “tricky” time for his parents.

Two years after Elijah’s birth, Fiona and Ben were back in the same maternity room, welcoming a baby girl.

“It was a completely different experience, both in the hospital and after,” Fiona said.

“My mum saw Amelia within 12 hours and was giving her newborn cuddles.”

The couple volunteered to take part in the Bicycle study because they want to help researchers understand exactly how the lockdowns affected the youngest members of society.

It’s hoped the results will help answer one pressing question – if it happens again, what should we do differently?